Mary and the journey to find peace

It’s the day before Christmas, which for many of us means a combination of last-minute gift wrapping and festive preparation. But my mind is not on that. As is the case at this time every year, I think primarily of one person: Mary, the mother of Jesus. And how, somewhere, a few thousand years ago, she was probably doing what women have been doing since the dawn of time: sweating and laboring to give birth to her baby. He is destined to bring about both conflict and peace.

I’ve thought a lot about Mary’s body, the role it played in this birth, the pain and exhaustion, all its excruciating trauma. Traditionally in art, nativity scenes show an unusually pale Mary or a blessed rosy Mother lovingly watching a nursing rosy-cheeked infant or a playfully cradled infant. holy court in the heart.

In those images, Mary is gentle, gentle and calm. It is very difficult to find in art history any image that matches my own image of Mary as a brave, strong, reflective and determined young woman who weighed the dangers and turning life upside down is required of her, before accepting the burden.

In my mind, Mary’s labor and birth seem to be of equal importance to every other part of the Christmas story. Especially in the past year, as one story after another celebrates the strength, courage and resilience of women around the world, from Ukraine to Afghanistan to Iran.

In “Annunciation of the Virgin” (1476) by the Sicilian artist Antonello da Messina, we encounter a rare picture of the Annunciation. There is no sign of the Angel Gabriel. A dignified, young Mary was alone, reading, most likely Hebrew holy texts, when she was disturbed by someone. Probably Gabriel, but also by us, the viewers. With her left hand, she modestly pulled the blue veil over her chest, but her right hand reached out as if to prevent anyone from disturbing her personal time.

Behind her is a dark void that offers no clues as to where she might be or what her past is. There’s no aura, no ghosting, nothing to suggest that she has any more special abilities than any other girl or woman (and we can be sure she isn’t). the only poor, young and unmarried virgin in the world).

I like this image of Mary because I assume she heard Gabriel’s invitation, and the gesture of her right hand shows that she needs a minute to accept. This Mary, reader and thinker, seems to be giving serious consideration. Will she take the seed of peace in her belly, nurture it, and sow it into a world of injustice and pain? I try to imagine her contemplating all that is at stake in her “yes”. Her pending marriage to Joseph, her reputation, her livelihood, not to mention huge political implications: the child will be given the throne of King David, which means upheava big society.

I suspect she is counting her participation costs. I like that she looks straight at us, alluding to us in Gabriel’s question. I can’t help but think of the women around the world today who are doing whatever they can to seek justice and peace for themselves, their families, and their communities. They shared with Mary a mixture of conviction, fear, strength, and courage.

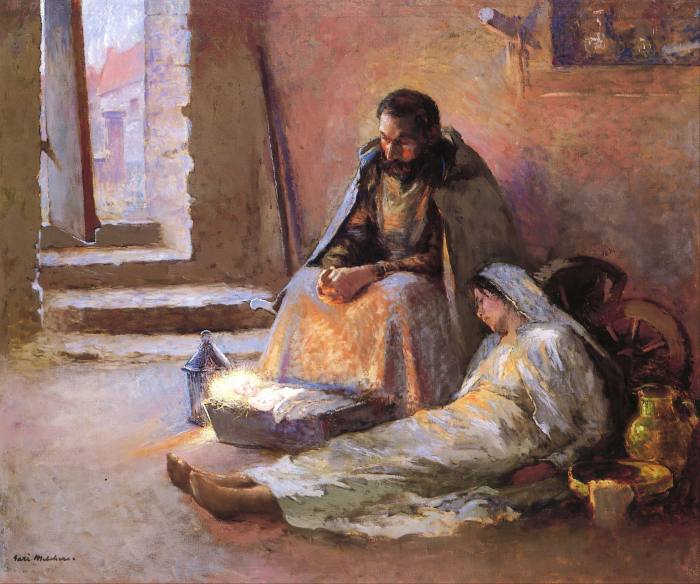

In the painting “Christmas” in 1891, American painter Julius Garibaldi Melchers tenderly but powerfully depicts the holy family shortly after Jesus was born. In a poorly furnished room lit by lanterns, an exhausted Mary collapsed on the bare hard floor. Joseph was gazing intently at the infant, in deep consideration.

‘The Nativity’ (1891) by Julius Garibaldi Melchers shows a thoughtful Joseph next to Mary © Alamy

We forget that Joseph, in this story, was probably the only one who helped with the labor. Surely he has his own fatigue. But he seemed to be basking in wonder and worry about this miraculous baby. Newborn baby lying on a makeshift bed. A bright orb of light surrounded his tiny head, illuminating the sleeping mother’s face and Joseph’s frame.

In this work we see only part of the consequences of Mary’s “yes”. Damage to her body, leaving the house, and uncertainty about what to do next. But what this image also highlights for me is that Joseph also said his own “yes.” He said yes to going beside Mary. He was her ally in this matter.

Mary’s strength was formidable, but perhaps she couldn’t do what she did alone. What does it mean for any of us to consider ourselves today’s peace collaborators, allies of women whose bodies are on the front lines of conflicts, according to the proverb and even literally? It’s funny how the word “peace” sounds so soothing and comforting. But achieving peace often requires a great deal of us, a degree of selflessness, sacrifice, resilience, and some capacity to see something better beyond what may be comfortable or easy for us. me as an individual.

In the past few months, the world watched the uprising for women’s freedom in Iran after Mahsa Amini, 22, died after being detained by the nation’s “moral police”. She was arrested for not wearing the hijab properly. Women in the country and across the diaspora have demonstrated by taking off their headscarves, cutting their hair and leading the way with the cry of “Women, life, freedom”.

Iranian artist Shirin Neshat has a history of using her work to highlight the status of women in her country. “Women’s Freedom Lives” is a public commission that was shown at Piccadilly Circus, London and Los Angeles in early October. The work was an adaptation of her 1995 work “Moon Song”, a part of the “Women of Allah” series, in which Neshat explores the complexities of women’s lives and identities after the 1979 Iranian revolution.

‘Freedom of a Woman’s Life’ by Shirin Neshat

It shows a woman’s hand, stretched out towards us, palm extended. The left palm is engraved with the inscription Farsi, an excerpt from the fantasy novel by Moniro Ravanipour drowned person, which Neshat says makes “an allegorical analogy between a storm under the sea and the political climate on land”. In the middle of the palm are two bullets, symbolizing the cost of the struggle. The palm of the right hand is painted with a large paisley pattern and flower petals. For Neshat, this speaks to Iran’s rich heritage. On hand, Neshat added the call of the current protests: “Women, Life, Freedom”.

There is no peace without work and without some expense, and that is not born of the labor and bodies of women in some way. Even God, who chose Mary, seems to recognize that. As we celebrate the season in different ways, perhaps we can reflect on what each person’s life will be like to be a peacemaker, to work towards peace. For what reason are we willing to say “Yes”?

enuma.okoro@ft.com; @EnumaOkoro

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first