Rebels confront the scandalous Big Four

The collapse of Enron in 2001 and the departure of auditor Arthur Andersen not only reduced the Big Five accounting firms to the Big Four, but also forced most of them to sell their consulting divisions within context of suppression of conflicts of interest.

Over the next 20 years, as the Enron scam went down in history, the teams rebuilt their consulting empires, advising on everything from debt defaults to cybersecurity. But now a scandal line again raised concerns that firms that sell services such as mergers and acquisitions also cannot function effectively as auditors.

That has forced Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC to rein in the side-selling activity that gave them $157 billion in combined annual sales last year – opening the door for nimble competitors to collect lure the stars to perform with well-paid checks.

Smaller insurgents, many of them backed by private equity, are bidding for the most lucrative parts of the Big Four business without being dragged along by low profit margins. , audit activities are highly regulated and potentially damaging to reputation.

“We don’t steal their lunches too much, we eat them,” said Richard Fleming, head of European restructuring at Alvarez & Marsal, a private firm that has hired more than 50 senior advisors. steal food from their cupboard that we wanted. from the Big Four in Europe since 2017.

But while the Big Four are reshaped myself In response, they are adamant, they will defend their part of the field. Jon Holt, UK CEO KPMG said just because they’re under attack “doesn’t mean the multi-industry model is dead”.

Everything but the audit

A Big Four company with volatile partners faces a choice similar to a football club negotiating with a “runaway” player: arrange a quick sale to raise cash and reshape themselves, or stand firm and run the risk that their team will fall apart without the financial cash. .

Smaller competitors with ambitious growth plans find that they can turn away Big Four partners who feel underpaid, unpopular, or limited in winning customers due to conflicts with the audit practices of the companies.

Both Deloitte and KPMG have promote sales of their UK restructuring divisions this year in deals backed by private equity groups CVC Capital Partners and HIG Capital respectively. Other business areas are also improving.

“We take care of everything but the audit,” said a US-based private equity executive who has worked with numerous professional services deals.

The transactions arrived densely and quickly. By PwC $2.2 billion processing of tax and immigration consulting firm last month for acquisition group Clayton, Dubilier & Rice by far the largest Big Four in recent years.

The group also sold a fintech business in the UK and parts of its consulting divisions in the US and Italy to private equity funds; while last year KPMG cut off the pension business for 500 people in the UK a £200m deal.

Independent US-based companies such as Alvarez & Marsal, AlixPartners and FTI Consulting are also hiring Big Four star practitioners to drive their global expansion.

‘We can recognize people’s achievements. . . ‘

Private equity funds and independent players are attracting partners with less promise the battle on the field, make faster decisions and invest in neglected areas – but the promise of more wealth is working for you, too.

High performers are able to keep more income than the traditional Big Four model, where service time is a key determinant of profitability.

Timothy Mahapatra, managing director at Alvarez & Marsal, said: “Younger, highly talented partners are growing increasingly impatient about seeing the right rewards for what they do. company profits. “We can recognize people’s achievements more easily.”

The Big Four companies have ramped up their recruitment of around 1.2 million people worldwide, with the resulting bureaucracy leaving some partners feeling disenfranchised.

“Once you’re at 600 partners, you don’t really have equity at that scale, you do,” said Mark Raddan, head of advisory at Interpath Advisory, a corporate restructuring firm. is the kind of employee to be honored. sold by KPMG to HIG This year.

But facing cash from private equity, the Big Four are optimistic about keeping the majority of their partners, arguing that their model offers steady income from diverse and relevant businesses. to help clients cope with changes caused by the pandemic, climate change and Brexit.

“You need a global multi-disciplinary company that answers those problems because they are not a short question they are asking you,” says Holt.

That is to say, executives at the Big Four say that sales are sometimes by choice. “It’s about cutting down the portfolio, making it possible to invest and then do other deals to achieve capabilities that we might not have at the moment on the scale. [we need] for the future,” said one global executive.

Sometimes the settlement works for both parties. Andrew Coles, managing director at Isio, the UK pensions division sold by KPMG, said his company has expanded more rapidly as an independent business through a recent acquisition. “Could it be that KPMG wrote the check? Of course they can. Can they do it? I’m not sure.”

Use

The success of several early buys has increased private equity interest. CVC nearly quadrupled its stake in AlixPartners between 2012 and 2016, according to two people familiar with the investment.

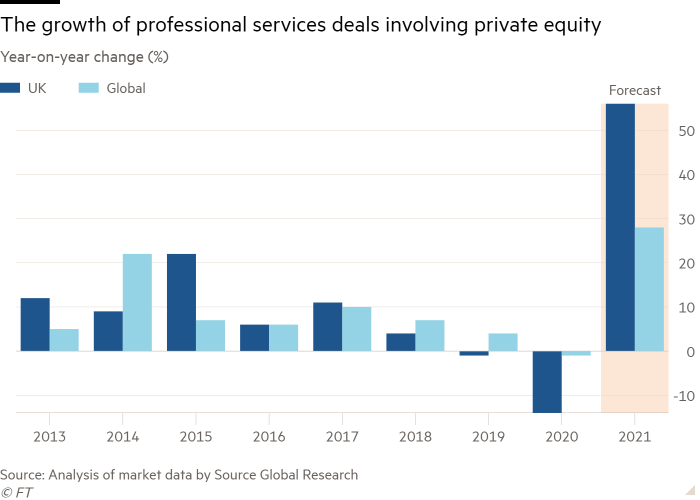

Globally, the number of professional services deals involving private equity groups has increased steadily since 2013, according to analysis by Source Global Research, a data provider for consultants. .

In the UK alone, they say market data shows there are more than 400 deals in 2020, a number that could more than halve this year based on current trends.

Buying groups also often avoid buying professional services businesses, in part because banks are wary of extending large amounts of debt to companies whose primary assets are people, rather than factories or machines. .

However, lenders have become increasingly accustomed to private equity financing to acquire specialist firms – and with an increasing amount of leverage – while companies have learned to retain those professionals. effective person, such as with callable stock options.

The risk is still real

But buying a business with human assets comes with risks. The two founders of Teneo, the CVC-owned public relations and consulting group that acquired Deloitte’s restructuring business this year, have left the company. in separate reputation crises within a few months of each other.

There is also commercial risk to newly spun off entities. Teneo’s $605 million in senior debt makes it more than six times more leveraged than its core earnings as of March of this year, according to Moody’s, reducing its ability to maneuver should things go wrong, according to Moody’s. .

According to people familiar with the terms, the HIG acquisition has valued Interpath at around £375 million, leading some rivals to question whether it can turn a satisfactory profit even as it expands. internationalization or diversifying into fields such as forensic accounting.

Glimpse of the recent acquisitions is the fact that the restructuring industry has been quieter than expected during the pandemic with the support of the government, banks and stock market all helping investors. business exists.

At the same time, competition is fierce: Seven or eight restructuring advisors can advertise a job, said one bankruptcy attorney.

Fiona Czerniawska, executive director of Sources Global Research.

Without the extensive global networks of Deloitte and KPMG, rivals argue that the new independent businesses at Interpath and Teneo may find it difficult to win big international tickets. The couple have set their sights international expansion But even if they succeed, it takes time.

“They can hire someone here or there but in the short to medium term they are weak competitors,” says Fleming, who led a group of partnerships from KPMG to Alvarez & Marsal in 2017. much more than yesterday.

Predator or prey?

Smaller competitors hounding their businesses have so far been unable to stop the Big Four’s growth. Three of the companies reported increase revenue this year with KPMG results to be announced in December.

And Big Four executives like to paint private equity raids as a normal cycle of creating and selling new businesses. They did buy business and build internally in the areas where they predict post-pandemic growth: technology, cloud computing, climate change, instilling cultural change in companies and purchasing advice – merger – according to them, what matters is choice rather than necessity.

But for the rebels, those moves don’t change the fact that the Big Four are prey: “I think they’re defenseless,” says Fleming.