The axis was blocked where dozens died

BBC

BBCWhen Mzwandile Mkwyi was lowered into the South African mine in a red metal cage attached to an above-ground crane, the first thing that struck him was the smell.

“Let me tell you something,” he told the BBC, “those bodies smell really bad.”

When he got home later that day, he told his wife that he could not eat the meat she had cooked.

“That’s because when I talked to the miners, they told me that some of them had to eat other things. [people] inside the mine because there was no way they could find food. And they are also eating cockroaches,” he said in a phone call from home.

Allegations that the miners resorted to cannibalism were also made by other miners rescued in December, in statements to the high court.

Mkwyi, a former prisoner, known locally as Shasha, lives in the town of Khuma near the abandoned mine in Stilfontein. The 36-year-old man, who served seven years in prison for robbery, volunteered to help with the rescue effort.

“I am being rehabilitated by correctional services and I volunteer because people in our community are looking for help for their children and brothers.

“The rescue company said they didn’t have anyone who wanted to come down. So, my friend Mandla and I agreed to volunteer to help our brothers surface and bring up the corpses.”

But even though he wanted to help, the 25-minute journey down to the 2km (1.2 mile) deep tunnel still terrified him.

AFP

AFPThe crane occasionally stopped and then started again, leaving him floating in the darkness. When he went down to the mine, he was shocked by what he saw.

“There were a lot of bodies, more than 70 bodies and about 200 people were dehydrated.

“I felt so weak when I saw them, it was a painful thing to see. But Mandla and I decided that we needed to be strong and not show them how we felt so we could encourage them.” .”

This story contains a video that some people may find disturbing.

The miners who had been waiting for help for months gave them a hero’s welcome.

“They were very, very happy,” he said.

Miners were trapped there after a nationwide police campaign to end illegal mining at closed disused sites, as the industry – once the backbone of The country’s economy – is shrinking.

It is no longer profitable for multinational mining companies to operate in many places, but the promise of still finding gold deposits has been a magnet for many desperate people – especially those Undocumented migration.

Thousands of shafts were abandoned.

In November, police stepped up efforts at the Buffelsfontein mine in Stilfontein, surrounding the entrance to the mine and refusing to drop off food and water.

Before the rescue operation began on Monday, the local community tried to take matters into their own hands by dropping a rope down the shaft to try to pull some of the men out.

They also sent messages and told the miners that help was on the way.

“So when we got there, they were waiting for the crane. Now when they saw us, they saw us as their presidents, as their saviors: people from the outside in.” hole to help them surface.”

Police said illegal miners could always go out on their own but refused to do so for fear of being caught. But Mkwyi disagrees: “It’s a lie that people don’t want to go out. Those people are in dire need of help, they are dying.”

While at the mine on Tuesday, the BBC witnessed dozens of people being rescued.

They appeared emaciated, their bones clearly visible through their clothes. Some people could barely walk and had to seek help from medical staff.

In statements submitted to the high court, illegal miners describe in graphic detail the slow and painful deaths of their colleagues. They said many people died of starvation.

“From September to October 2024, the lack of basic nutrition was absolute and survival became a daily fight against starvation,” one miner was recorded saying.

Mkwyi said the men he rescued were so weak that a rescue cage meant for only seven healthy adults could hold 13 of them.

“They were very dehydrated and losing weight so we tried to put more in the cage, because they wouldn’t be able to survive another two days in the hole. They will die if we don’t get them out as soon as possible.” .”

Volunteers are also responsible for removing dead bodies.

“The rescue services gave us bags and told us to put the bodies in them and put them in cages. We did it with the help of some miners.”

The rescue operation was initially expected to last at least a week, but after just three days, volunteers said no one was left underground.

Authorities sent a camera down the shaft to perform a final review. They say the mine will now be permanently blocked.

But the experience had a profound impact on Mkwyi.

At one point in the call, he asked to repeat a question, explaining that his hearing had been affected since going down the mine, perhaps due to the pressure.

But the heaviest impact came from what he witnessed.

“I have to tell you, I’m devastated. I will never forget the sight of these people for the rest of my life.”

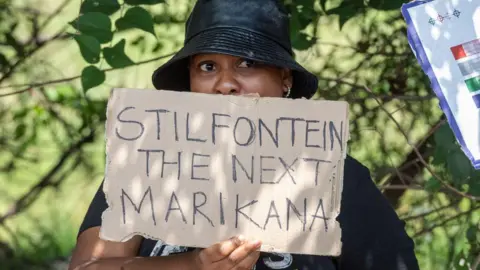

For activists and unions helping the community, the deaths of 87 people in the mine amounted to a “massacre” carried out by the authorities.

The use of emotive words brought out the comparison Police shot dead 34 striking miners in Marikanaapproximately 150km (93 miles) from Stilfontein, in 2012.

But this time no trigger was activated. Instead it seems many people starved to death.

The authorities rejected the idea that they were responsible.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government initiated a crackdown on illegal mining in December 2023 through Operation Vala Umgodi (which means “close the loophole” in isiZulu).

Abandoned mines have been taken over by gangs, often led by former employees, who sell their finds on the black market.

People are forced into this illegal trade, by force or voluntarily, and are forced to spend months digging for minerals underground. Illegal mining cost the South African economy $3.2 billion in 2024 alone, the government said.

As part of the police operation, entry points at various disused mines were blocked, along with food and water supplies, in a bid to chase away illegal miners, supported by residents. Locally called zama zama (roughly translated as “take a chance”).

While Vala Umgodi has been largely successful in other provinces, the old Buffelsfontein gold mine posed a particular challenge.

Before the police operation, most miners could only go underground through a temporary pulley system operated by people on the surface.

But they later abandoned the upper part of the mine when security forces arrived in force in August, trapping those in the mine.

Community members then came to help, using ropes to pull some people up, but this was a long and arduous process.

Other difficult and dangerous escape routes became available and in total nearly 2,000 exits reappeared – most were captured and remain in police custody.

Why the others didn’t come out is unclear – they may have been too weak or were threatened by gang members in the mine – but they were left in desperate circumstances.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOf the 87 dead, only two have been identified, police said Thursday, explaining that the fact many were undocumented migrants made the process more difficult.

Magnificent Mndebele, from the Mining Affected Communities Action Group (Macua), told the BBC: “We maintain the view that the government has blood on its hands.”

He argued that the miners were not given advance warning of what was about to happen before the police operation began.

Over the past two months, Macua has been at the forefront of various court battles launched to force the government to first allow supplies and then launch a rescue operation.

Blaming the government echoes previous statements by families who said authorities killed their loved ones.

They have taken a hard line since the increased activity. In November, a minister, Khumbudzo Ntshavheni, infamously announced at a press conference that they would “suck them away”.

The state refused to allow food to be sent down or anyone to help retrieve the miners, only giving in after several successful court applications.

In November, a small portion of instant corn and water was taken down the shaft, but in a statement to the court, one of the miners said that amount was not enough for the hundreds of men below, many Some of them are so weak that they cannot chew and swallow. Surname.

More food was delivered in December, but again it failed to feed the men.

Given that the operation to remove the men and bodies lasted only three days, what puzzles Mr Mndebele is why it could not have been done sooner, when it was clear there were problems.

“Frankly, we are disappointed in our government because this help has come too late.”

While the government is yet to officially respond to these allegations, police have vowed to continue broader operations to clear the country’s disused mines until May this year.

Speaking to journalists in Stilfontein on Tuesday, Mining Minister Gwede Mantashe was unrepentant. He said the government would step up its fight against illegal mining, which he considered a crime and an “attack on the economy”.

On Thursday, Police Minister Senzo Mchunu appeared a bit more conciliatory.

He said: “I understand and accept that this is an emotional matter. Everyone wants to judge… but it would help all of us, as South Africans, to wait until the pathologists have finished their work.”

Police have defended their actions, saying providing food to the miners would “enable crime to thrive”.

Illegal miners have been accused of promoting crime in the communities where they operate.

Several stories have been published in local media linking zama zama to various rapes and murders.

But for Mkwyi, who put his own safety first to help the miners, the men at the Stilfontein mine were just trying to make a living.

“People go down 2km on ropes and risk their lives to put food on the table for their families.”

He said he wants the government to issue licenses to artisanal miners forced into abandoned mines due to South Africa’s high unemployment rate.

“If your kids are hungry, you won’t hesitate to go down there because you have to feed them. You’ll risk your life to put food on the table.”

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC