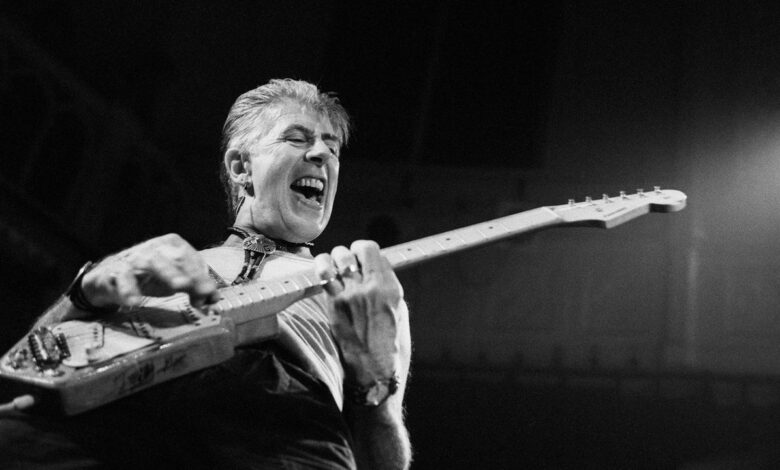

Blues legend John Mayall dies at 90

“Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Blake, Blind Boy Fuller… all the blind boys.” That’s how multi-instrumentalist John Mayall, one of the main architects of the British blues revival of the 1960s, who died yesterday at the age of 90 at his home in California, described it. describe the effects shaped his musical tastes and inspired a career that spanned six decades. That career, which began long before Mayall formed his seminal Bluesbreakers in 1963, was defined not by bigotry but by a singular, almost messianic vision that the music made by black artists in the Mississippi Delta and the South Side of Chicago possessed a beauty, honesty, and power that transcended race, age, and geography. And so, thanks to Mayall—along with like-minded musician Alexis Korner and a growing number of fans—American blues took root in London’s coffeehouses, the traditional home of jazz. From there, it migrated to underground clubs packed with sweaty young men, and to record players and radios in apartments from Bournemouth to Belfast.

Soon a generation was drawn to the explosion of the British R&B scene: the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, Them, and many more bands, including Cream and Fleetwood Mac, two era-defining rock bands that Mayall helped shape. The blues-centric vision that Mayall brought to popular music in the 1960s turned out to be 20/20.

In the 21st century, discussions of the British blues boom have focused on these important foundational aspects—and raised difficult questions about cultural appropriation. But there is no doubt that Mayall’s admiration for the blues was sincere and unquestioning, not to mention daring, pioneering, and subversive—a significant dent in the armor of postwar, hard-edged, class-divided Britain. As Mayall and other evangelists brought the work of Otis Rush, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, and Elmore James to hungry young audiences across the Atlantic, these blues legends began to find themselves sought after as concert attractions, sought out as musical mentors, and celebrated as cultural icons in Europe, America, and, in time, across the globe.

John Mayall was born in 1933 and grew up in the town of Cheadle Hulme, a suburb of Manchester. His parents divorced when he was a boy. Mayall’s most famous childhood feat was building a treehouse out of window frames and canvas in a sturdy oak tree behind his mother’s house, furnishing it with a bed and a kerosene lamp. “It became my room, my world,” he said. (In 1970, he wrote a song about it, “The tree house.”) His father turned his interest to jazz guitar, and Mayall, then 12, began playing the instrument along with the piano. By the late 1940s, he had become enamored with jazz, recording 78s. And then he stumbled upon the blues—a genre that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

As a white suburban kid growing up in post-war Britain, listening to the blues exposed Mayall to the genre’s outsized personalities and the harsh conditions they often sang about. As Mayall tells it, Guard In 2021, “The so-called ‘racial profiling’ told the story of brutal lynchings and racial injustice in the South, which was the reality of being a black man in the early 20th century. Not many other people I know were really interested in this genre of music, but it was something I was really passionate about.”

In 1956, Mayall returned from military service in Korea to attend art school in Manchester, forming his first band, the Powerhouse Four. Then came the Blues Syndicate, which moved to London in 1961, where Mayall met Korner, who encouraged him to move south. Mayall plunged into the London blues scene, forming the Bluesbreakers and becoming a mainstay at clubs like the Marquee. If the blues-soaked Rolling Stones were on their way to international pop stardom, the Bluesbreakers were musicians’ musicians, all about integrity—the spirit of the blues. They were the perfect band for the blues enthusiast who collected records, a group that would never be swayed by big commercial success: purists, not tourists.

Mayall’s Bluesbreakers were a melting pot of generational talent. Eric Clapton left the Yardbirds and joined the band; his playing was featured on the band’s debut album, released in 1966. When Clapton left, Peter Green, later to form Fleetwood Mac, joined. And when Green left, Mick Taylor, later to form the Rolling Stones, joined. Mayall was to British blues guitarists what Leo Castelli was to New York artists; his group was the high-end art gallery you’d want to show your work to. Bassist Jack Bruce met Clapton in the Bluesbreakers, then went on to form Cream. Other future rock stars were former Mayall members: Mick Fleetwood and John McVie, later to form Fleetwood Mac, and veteran drummer Aynsley Dunbar. During these Bluesbreakers formations, and many others that followed, Mayall switched between guitar and keyboards, with notable moments demonstrating his harmonica playing. Mayall’s main talent, though, may have been his uncanny and unselfconscious ability to spot talent in others.

In the late ’60s, Mayall moved to California, moving into a house in Laurel Canyon that became affectionately known as The Brain Damage Club, based on the type of personalities and entertainment one could find there. The house burned down in the 1979 Kirkwood Bowl-Laurel Canyon fire, which destroyed Mayall’s entire archive, along with the vintage porno treasure his father had amassed. (“My dad was a porno collector,” Mayall says without hesitation. “A collection that is absolutely irreplaceable.”) Over the following decades, there were more concerts, tours, collaborations, and albums, as Mayall became known as the Godfather of British Blues. In 2005, he was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. A 35-disc box set of Mayall’s work was released in 2021. Three years later, at the age of 90, he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Mayall was married twice; he has six children and several grandchildren.

A cornerstone of the Mayall song collection is “Room to Move,” driven by impulse, almost harmonica madness. But if there’s one song that defines him, it’s probably “All Your Love,” a classic Chicago blues song mixed with Otis Rush mambo that was the calling card of the Bluesbreakers and an early performance for Clapton. fireworks guitar(Peter Green recast “All Your Love” as “Black Magic Woman,” which became a 1968 Fleetwood Mac single and later became a Carlos Santana signature song.)

In February 2020, on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic, Mayall, who is still spry at 86, sang “All Your Love” passionately at the London Palladium as part of an all-star tribute concert organized by Mick Fleetwood to honor Green’s music. (Green died about five months later.) It would be difficult to estimate how many times Mayall performed that song and others like it—usually three-chord, 12-bar blues—and how many times he performed them.

When a reporter asked John Mayall about his unwavering loyalty to the blues, the music that took him from a treehouse in suburban Manchester to concert stages around the world, Mayall replied, “I can’t play anything else.”