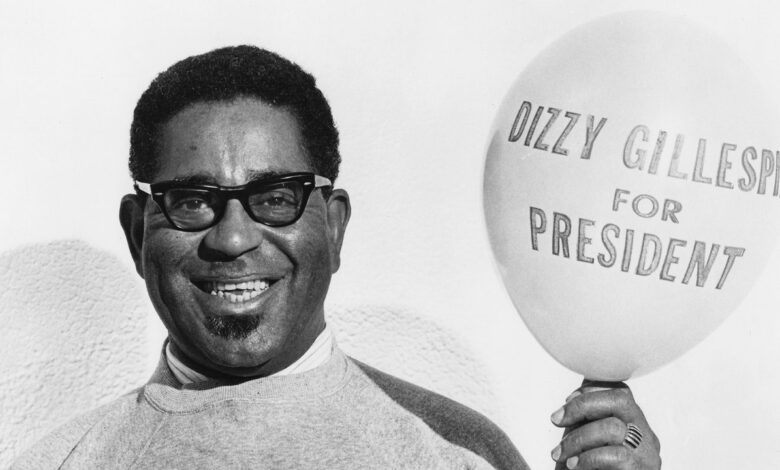

Dizzy Gillespie Runs for President! Revisiting the Jazz Giant’s Quixotic 1964 Campaign

A quiz for the 2024 election. Who is the most popular—not to mention entertaining—third-party presidential candidate in American history? The answer is not comedian Pat Paulsen (who ran multiple times from 1968 on). Not Ross Perot (in 1992 and 1996). Not Ralph Nader, Jill Stein, Kanye West, or even madness, confusion Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

The answer is John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie, the legendary jazz trumpeter, composer, and reformer who ran as an independent in 1964 against incumbent Democratic candidate Lyndon B. Johnson and far-right Republican candidate Barry Goldwater.

Throughout his more than 50-year career, Gillespie has been hailed not only as a great jazz musician—a true giant of the genre—but also, like Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller before him, as a masterful entertainer. In fact, the greatest jazz pianist of all time Bill Charlap commented, “Dizzy was so funny on stage that it often obscured what a talented and wonderful musician he was.” The 93-year-old saxophonist Sonny Rollins, Dizzy, who worked regularly with him, agreed, telling me that the public viewed Gillespie much as they viewed Armstrong, “as an entertainer, almost a comedian, as well as a musician.”

In his memoirs, Yes or no…Bop, Gillespie claimed that his presidential campaign “began largely as a result of the 1963 Washington March for Jobs and Freedom and the Newport Jazz Festival.” However, he had been actively campaigning—with signs and placards, no less—since at least early February of that year at the Blackhawk nightclub in San Francisco, even before Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic march in August 1963. was formed“It wasn’t just a publicity stunt,” he later wrote in his memoir. “I gave campaign speeches and rallied people. I really wanted to see how many votes I could get and how many people thought I would make a good president.”

Gillespie’s politics also came to the fore. For much of 1963, his performances were a mix of his usual modern jazz routines, including original standards such as “One Night In Tunisia” and “Con Alma,” interspersed with semi-serious campaign rhetoric. By September, the campaign—by then headed by Jean Gleason, wife of Ralph J. Gleason, the jazz critic who later became the founding editor of Rolling Stone—was in full swing. That month, when Gillespie played at the sixth Monterey Jazz Festival, Downbeat reported that not only was “Dizzy for President” merchandise given away and sold throughout the festival, but Gillespie and Gleason collected more than 1,000 signatures on a petition to officially put him on the California ballot.

Legendary bass player Ron Carter, now 87, was a member of Miles Davis’s great quintet at the time, and also played in Monterey that year. “We all took it as a joke,” he said of Gillespie’s campaign. “As individuals, we’re often asked to play to raise awareness about presidential candidates. Dizzy’s ‘candidate’ was to let people know that we weren’t just playing music—we had our eyes on who would be the next president.”

A few weeks later, the candidate was asked to speak at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, largely answering questions from the crowd that had been written in advance and then read by Gleason. Gillespie spoke authoritatively on such topics as whether foreign-born musicians could compete with their American counterparts (he answered yes—in a roundabout way) and the impact of alcohol and drugs on a musician’s playing (he was adamantly against them). When asked whether jazz had lost its sense of fun when it became a protest music, Gillespie said: Downbeat, He had a convincing and profound answer: “Jazz is said to be able to express all human experiences – anger, laughter, joy and sadness.”

At the time, the ultraconservative John Birch Society was on the rise. And Gillespie’s candidacy was, in its own way, an attempt to push back against both the political establishment and the rise of divisive forces in American life. Indeed, rather than condemn the far right, the ever-tolerant Gillespie admitted that he would be open to considering a “John Bircher” in his Cabinet. “You see,” he said, “we need opposition.” At another point in the campaign, his supporters began calling themselves the “John Birks Society”—both a counterpoint to conservatism and a coded reference to his own name.