Erik Rivera talks about comedy as a healing process

During Mental Health Awareness Month, we asked Latinx comedians and creators we admire how comedy has helped them overcome trauma and face their most important challenges. how in life. Read the sections here.

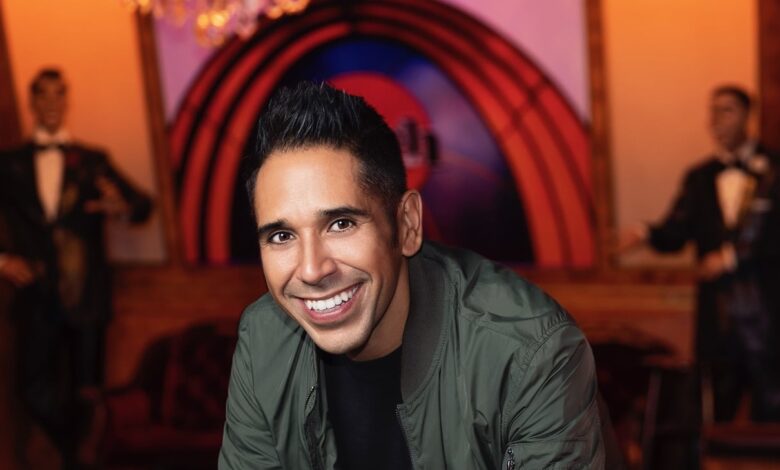

Erik Rivera’s life is good. Joining our Zoom session from his Los Angeles home, the writer, actor and comedian were all smiling under his donned baseball cap. Maybe it’s the sunny weather that Angelinos always brag about. Or maybe it’s the fact that he worked hard to achieve what he has now: a respectable career, a stable marriage, and two wonderful sons. Regardless, the contrast between where he once was and his current situation is not lost on him, even if it is not with his children.

“My kids don’t know how good they have it,” the comedian said with a laugh.

Growing up as the child of a Puerto Rican father and a Guatemalan mother in New Rochelle, NY, Rivera understood well the value of the dollar. He spent his younger years bouncing between his parents’ immigrant sensibilities and the pressures of life in America. Unsurprisingly, that dichotomy is something that Rivera was able to mine for comedic gold, incorporating it into his perspective along with other aspects of his life, like his marriage. interracial marriage and what raising two boys is really like. However, despite his lifelong passion for stand-up, comedy as a career wasn’t something Rivera saw in the cards.

“When you come from immigrant parents, you don’t know that it’s a career,” Rivera said. “You’re forced into conventional jobs, like doctors, lawyers, and told, ‘Do it. something that is consistent and brings in a steady amount of money'”. So Rivera plans to attend Pace University to get a degree in communications. Then 9/11 happened.

“[After 9/11]they have reopened [the school] because they used the campus as a sorting center. And I remember coming back, and it was just a strange feeling. There is soot everywhere. We are seeing trucks carrying waste out every day. The kids just felt uncomfortable,” Rivera recalled.

In an attempt to escape the morbid atmosphere, Rivera and a friend went to a comedy club, where they were shocked to find it packed.

“People want to forget,” the comedian said plainly. He then came up with the idea of organizing a comedy night on campus and creating an opportunity for his students to come together and heal their wounds with laughter.

“Stand-up comedy is a pure art form…no matter what you’re going through during the day, you go to a show, and for an hour and a half, the problems you have, you let they’re there. the door and you have a good time,” Rivera said. “Yes, they will still be there [when you leave]But you can relax and relieve yourself.”

But while helping others overcome trauma by hosting comedy shows is great, part of Rivera wants more. As a child, he saw John Leguizamo’s “Mambo Mouth,” which immediately sparked something in him. Here was someone from his culture, talking about things he could relate to. Now as an adult, hosting stand-up nights and encountering comedians, he’s had the opportunity to tell his own story and use it to help people accept theirs.

“I remember sitting one night [at a comedy show], and this was the first time I saw how the rabbit was pulled out of the hat. Like, I see the setup, I see the ending, I see the way the guy leads the audience in one direction and plays with their emotions of frustration, anger and releases it with laughter,” “I was like, ‘I think I can do this,'” he said.

A month later, he appeared on the stage of Harry’s Hamburger club in Times Square. For most of us, the thought of just jumping off a cliff like that is incomprehensible. But for Rivera, that’s what makes the monologue performance so special. It’s not just about telling jokes, it’s about expressing yourself – revealing your pain and difficulties to serve the audience.

Rivera said: “Look, you can go up there and write jokes; There are some great joke writers out there.” “But [the real connection comes] out of the hole. Yes, we find that through stereotypes, but there’s also the vulnerability of ‘hey, this is happening to me’ and people can relate to that.”

For him, comedy is an escape, a way to explore certain aspects of his life that aren’t always neat or pretty, whether it’s his mother-in-law offering to host a Mexican mariachi band for Rivera’s rehearsal dinner or makes a point to keep. the refrigerator is filled with guacamole just for him. Exploring these issues on stage allows him to not only process them in a healthy way, but also take the audience on the journey with him.

This is why stand-up comedy has traditionally been a path to success for oppressed or marginalized communities. Our difficulties can create laughter, helping to lighten the burden we are carrying. But dealing with that pain can be difficult. Rivera admits he made the mistake of trying to explore certain traumas before they were fully healed — specifically, his father’s death from Parkinson’s disease.

“I’m not going to lie to you, when I first started doing that story on stage, it was difficult. I wasn’t ready to start talking about it,” he said.

But then something good happened. The more Rivera worked on the material, the more he refined his father’s story, and the more people started coming up to him after shows to thank him and tell him they were going through it too. something similar.

“Whenever you go through something, you feel like ‘I’m the only one going through this.’ We are all going through it; it’s just that no one talks about it,” he said.

For this reason, writing became part of Rivera’s healing process. Even if he hasn’t moved on from what he’s going through, even if he can’t see the humor yet or isn’t ready to take it to the stage, his mind is always searching for the opportunity to one day something could happen. he will be able to share it. He kept a diary regularly, seeing it as a kind of “map” of how he got through difficult times. The comedian also mentioned the important role plays play in helping him process his thoughts.

“Everyone should have some quiet time or meditation or something to help you get out of your head and into your own space,” Rivera said.

Whether it’s handling material on stage or running in beautiful Los Angeles weather, Rivera has it all his own. Throughout our conversation, he exuded an air of confidence that comes from doing his best, which he actually was working on himself. Now, he’s ready for what’s to come, even if it isn’t necessarily a comedy.

“You always have to evolve, man,” he said. “You have to do everything, you have to write, you have to direct. The more tools you have in your toolbox, the harder it is for them to say no to you.” .”

Rivera does all of those things. During the pandemic, he wrote an animated show that he wants to shop in the future. And while he still loves comedy and shares that it will always be his way of healing and helping others heal, he also acknowledges that there are more ways to tell important stories.

“Having children changed my perspective on everything,” he said. “Watching television and not seeing representation there, where my kids don’t even see themselves… now I’m moving in the other direction, let’s write these next TV projects so they I can see myself there.”

Rivera wants to see more of the stereotypical Latino stories about “cross-border trauma” or “we have to save the taco shop.” He just wants to see regular shows about Latinos as regular people facing regular problems, dealing with those problems the same way he has and continues to do.

“That’s my next goal in life,” he concluded, “to create these shows that people can laugh together, watch together and vibe with and just happen to have Latinos in them.”

Miguel Machado is a journalist with expertise in the intersection of Latino identity and culture. He does everything from exclusive interviews with Latin music artists to opinion pieces on issues relevant to the community, to personal essays tied to Latinidad his, as well as thoughts and characteristics related to Puerto Rican and Puerto Rican culture.