Proponents of eating insects face a culinary challenge: taste.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Think of it as cricket cake, fish cake,” the chef said as he urged the man at the buffet to try the spicy laksa – a coconut noodle-based broth – filled with “textured cricket protein.”

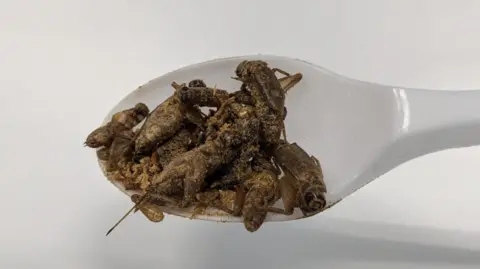

Next to it is a plate of chilli crickets, the insect version of Singapore’s favourite dish – stir-fried mud crabs drizzled with a rich sweet chilli sauce.

It looks like any other buffet, except for the main ingredient in every dish: crickets.

The line features a woman carefully scooping stir-fried Korean noodles with chopped crickets onto a plate, and a man constantly asking questions of the young chef.

You’d expect the diners to be quick to grab a bite. After all, they’re among more than 600 scientists, entrepreneurs and environmentalists from around the world who have descended on Singapore as part of a mission to turn insects into delicious food. The conference’s name says it all – Insects Feed the World.

And many of them were drawn to the buffet alongside the insect-filled dishes. Some considered it the usual fare: wild-caught grouper marinated in lemongrass and lime, grilled beef tenderloin with onion jam, coconut vegetable curry.

According to the United Nations, around two billion people, or a quarter of the world’s population, now consume insects as part of their daily diet.

According to a growing group of insect advocates who promote insects as a healthy, green option, more people should be getting on board. But is the prospect of saving the planet enough to get people to sample their top creepy crawlies?

the insect

“We had to focus on making them delicious,” said New York chef Joseph Yoon, who designed the cricket menu for the conference, along with Singaporean chef Nicholas Low. The event was allowed to use only crickets.

“The idea that insects can be sustainable, nutritious, can solve food security problems, etc.,” he added, “is not enough to make them palatable, let alone appealing.”

Studies have found that just six crickets can meet a person’s daily protein needs. And raising them requires less water and land than raising livestock.

Some countries have promoted, if not promoted, the insect diet. Singapore recently approved 16 species of insects, including crickets, silkworms, grasshoppers and honeybees, as food.

It is one of a handful of countries, including the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and Thailand, that are regulating a still-fledgling edible insect industry, estimated to be worth between $400m and $1.4bn (£303m and £1.06bn).

Insects feed the world

Insects feed the worldChefs like Nicholas Low have had to find ways to “decompose” insects to prepare them as dishes because people don’t always want to try them “in their original form.”

During the conference, Mr Low reinvented the popular laksa dish by replacing the usual fish cakes with minced crickets.

He said it also took some effort to mask the earthy smell of the insects. Dishes with “strong flavours”, like laksa, were ideal because the flavour of the original recipe distracted people from the crushed insects.

Crickets, Mr Low said, don’t leave much room for experimentation. Often deep-fried to a satisfying crunch or ground into a fine powder, they, unlike meat, can be prepared in a variety of dishes, from stews to roasts.

He can’t imagine cooking with crickets every day: “I usually cook it as a special dish that’s part of a larger menu.”

Since Singapore approved the cooking of insects, some restaurants have tried their hand at it. One seafood restaurant has started sprinkling crickets on satay and squid ink pasta, or serving them as a side dish to fish head curry.

Of course, there are others who are more committed to the challenge. Tokyo-based Takeo Cafe has been serving insects to customers for the past 10 years.

The menu includes a salad with two Madagascar cockroaches nesting in a bed of leaves and cherry tomatoes, a large scoop of ice cream with three tiny grasshoppers perched on it, and even a cocktail with wine made from silkworm poop.

BBC/Kelly Ng

BBC/Kelly Ng“The most important thing is [the customer’s] “Curiosity,” said Saeki Shinjiro, Takeo’s director of sustainability.

What about the environment? “Customers don’t care that much,” he said.

To be safe, Takeo also has an insect-free menu. “When designing the menu, we always keep in mind not to discriminate against people who do not eat insects… Some customers just come here to hang out with friends,” said Shinjiro.

“We don’t want such people to feel uncomfortable. There’s no need to force them to eat insects.”

Our food and us

However, it wasn’t always this way. For centuries, insects have been a valuable food source in many parts of the world.

In Japan, grasshoppers, silkworms and wasps are commonly eaten in inland areas where meat and fish are scarce. Takeo’s manager, Michiko Miura, said the practice was revived during food shortages during World War II.

Today, crickets and silkworms are commonly sold as snacks at night markets in Thailand, while diners in Mexico City pay hundreds of dollars for ant larvae, a delicacy once considered a delicacy by the Aztecs, who ruled the region in the 15th and 16th centuries.

But insect experts fear that these culinary traditions are being lost due to globalization, as insect eaters now associate the diet with poverty.

Joseph Yoon, a New York-based chef, said there was a “growing sense of shame” in places with a long history of insect consumption, such as Asia, Africa and South America.

“Now, they can learn about foreign cultures through the Internet and they feel ashamed to eat insects because it is not a common practice elsewhere.”

Insects feed the world

Insects feed the worldIn her book Edible Insects and Human Evolution, anthropologist Julie Lesnik argues that colonialism has deepened the stigma against eating insects. She writes that Christopher Columbus and members of his expedition described Native Americans’ consumption of insects as “a barbarity… greater than that of any beast on the face of the earth.”

Of course, people’s attitudes can change. After all, delicious foods like sushi and lobster were once foreign concepts to most people.

Sushi was originally a working-class food found on street stalls. And lobster, known as the “poor man’s chicken,” was once fed to prisoners and slaves in the northeastern United States because it was so plentiful, says food researcher Keri Matiwck of Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

But as transportation networks made travel easier and food storage improved, more and more people became aware of the crustacean. As demand increased, so did its price and condition.

Foods that were once considered “exotic” or even not considered foods can gradually become popular, says Dr Matwick.[But] Cultural beliefs take time to change. It will take time to change the perception of insects as disgusting and dirty.”

Some experts are encouraging people to raise their children to tolerate a wide range of exotic foods, including insects, as future generations will bear the full brunt of the climate crisis.

Insects could become the “superfood” of the future, coveted like quinoa and berries. They could be eaten reluctantly, rather than sought out for the pleasure of a buttery steak or a hearty bowl of ramen.

Right now, Singaporean chef Nicholas Low believes there’s no reason for people to change their diets, especially in wealthy places where almost anything you want is just a few clicks away.

Young consumers may want to try them out of curiosity, he said, but the novelty will quickly wear off.

“We are spoilt for choice. We like meat as meat, and fish as fish.”