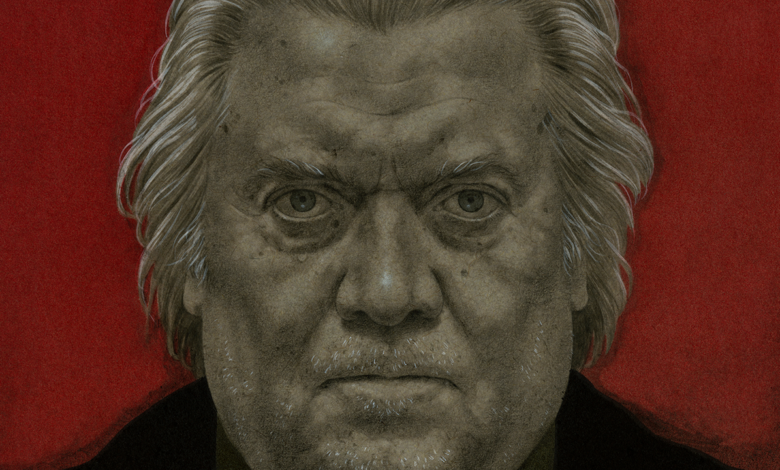

Steve Bannon has called his “Army” to war – No matter who wins in November

TThis is the time when Washington still felt like it always did – a sleepy little town in the South. Generations of the most powerful people on earth have spent their days in DC understanding that the city is a backwater. But Washington’s modest position in our group of great cities has always been part of its charm, well suited to our vast continental republic. American power has no center, or rather, it has centers everywhere—New York for finance, Houston for energyshort Menlo Park and Atherton Center, Californiabecause technologyback to the elite schools of New England, where our scribes and aristocrats were trained to manage the subsystems that kept the American project running. America, as many of the world’s most powerful people are now wondering, may suddenly feel like the Roman Empire entering a period of chaos and decline. But America never had Rome.

The DC area has grown dramatically in population, wealth, and importance since the end of the Cold War. Its new status as the capital of an unchallenged and free-spending global hegemon has made the region one of the world’s wealthiest metropolitan areas. Washington even boasts an infrastructure befitting its status as the administrative center of an empire, as policy elites now colloquially say – one that depends heavily on the money and information as well as on rudimentary military force. A cluster of cables and data centers in northern Virginia now routes much of global internet traffic through modest suburbs like Tyson’s Corner, where experts at the National Security Agency can monitor contact information conveniently. But last July, Washington felt largely unprepared to host such an event NATO 75th Anniversary Summit.

The city is suffering from two types of heat. The first is a windless humidity dome and 100-degree days that make even a short hike torturous. The second is that the heat will soon flare, making the month likely to be remembered as the most dramatic and consequential in our contemporary political history. But the news is back a president was almost assassinated And another may withdraw from the race These are just the clearest tremors of a geological shift that is upsetting a system maintained by “the most successful alliance in history,” as NATO’s Norwegian secretary general has described it. .

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, NATO leaders were in near-universal agreement, saying that the US-led apparatus that had given Washington new wealth and importance faced an existential risk. President Joe Biden said it was “a great fight for freedom.” “A war between democracy and autocracy, between freedom and repression, between an order based on rules and one ruled by force.” The theme of this year’s meeting is solidarity, standing up to challenge America’s ability to set the rules governing security and stability around the world. But just a short, sweaty walk from the mountaintop, a surreal “DC split screen,” as one Politico reporter described it, is taking place at the Capital Hilton — where insurrectionists and critic of this system speaking at the National Conservatism Conference (NatCon) . The foreign policy buzzword is multipolar—a dry-sounding term that suggests an epochal shift away from a world where the United States and its allies have control over practically all financial, military, and technology. Policymakers in Washington are looking to China and talking in almost panicked terms about how unprepared America is for a new era of great-power conflict. The Ukrainian army will soon be outnumbered five to one in areas of the Donbas front. As leaders and delegations from 32 member nations began arriving at Andrews Air Force Base, fear grew that half the American electorate was lining up behind one building. America First The movement has championed this multipolar vision as one that can benefit regular Americans at home, even as it costs us our overwhelming power abroad. War raged on the periphery of the empire. But the more pressing concern is that America may soon have a government run by people who want to overthrow it from within. “Unity, determination, purpose, all those good things,” one highly placed European delegate told me privately. “That’s the purpose of the show. But there’s clearly a giant question mark hanging over the whole issue of what happens in November.”

The night before the summit began, I went drinking at the Old Ebbitt Grill, overlooking the White House, with a friend who works for a defense contractor. “This is crazy,” she said, referring to the frenzied mood that was sweeping the town. “Everyone was so stressed it felt like they were going to explode.” But this isn’t just a vibe. It is a response to the very real risk of a shock to the world order. “I think people don’t fully appreciate that these institutions really can’t function,” Ben Rhodes, who was President Barack Obama’s most important foreign policy adviser, told me later. This. He said the world was “two-thirds of the way to a new world war.” But a shock can occur even without that. “The G20, the IMF, the World Bank, NATO—it is not the United States that is the biggest stakeholder,” he continued. “They are really appendages of the United States, our interests and our system. When we act as disruptors of our own empire, the system will be completely turned upside down.”

TWhat is his? populismcoming from left or right, really makes sense. That’s when voters have the power to weigh in on topics that politicians and policy experts want to keep out of the public debate.

This may sound like simple democracy, but in reality it is not how the democracies at the core of the American system, from France to Japan to our own, actually work. dynamic. The politicians, business titans and heads of think tanks who make policy for these democracies tend to fear, justly, that if voters have too much of a say in state management problems, they will push the entire society into chaos.

The first major disruption of this era came in 2016, the year of the Brexit vote, when British Prime Minister David Cameron called for a referendum on Britain’s membership of the Union. Europe, confident that the party that represents integration, a global and interconnected future, will advance itself. , will easily win. He hoped to resolve internal conflicts within his Conservative Party between technocratic liberals like himself and a group of traditionalists and nationalists. Instead, he lost and stepped down.