Syrians returning home face the deadly threat of landmines

Idlib, Syria

BBC

BBCAyghad never thought his dream of returning to his farmland could turn into a nightmare.

He fought back tears as he showed us a photo of his late father, smiling and surrounded by rich olive trees on their land in northwestern Syria’s Idlib province.

The photo was taken five years ago, months before forces linked to the former government took over their village, near the city of Saraqeb.

The city was a strategic stronghold of the Syrian opposition for years, before forces allied with Bashar al-Assad’s fallen regime launched an offensive against rebels in Idlib province in late 2019. .

Hundreds of thousands of residents were forced to flee their homes when Assad’s forces took over several other rebel strongholds in the northwest in early 2020.

Ayghad and his father were among those displaced.

“We had to leave because of fighting and air strikes,” Ayghad said through tears. “My father refused to leave. He wanted to die on his land.”

Father and son have longed to return ever since. And when opposition forces regain control of their village in November 2024, their dream is about to come true. But disaster soon struck.

“We came to our land to harvest some olives,” Ayghad explains. “We traveled in two separate cars. My father took a different route to return to our home in Idlib city. I warned him but he refused to let me. His car crashed a mine and exploded.”

Ayghad’s father died at the scene. That day he not only lost his father but also lost the family’s main source of income. Their farmland is 100,000 square meters, filled with 50-year-old olive trees. It is now designated as a dangerous minefield.

According to the Halo Trust, an international organization specializing in the clearance of landmines and other explosive devices, at least 144 people, including 27 children, have been killed by landmines and unexploded war remnants since their creation. Bashar al-Assad’s regime collapsed in early December.

The Syrian Civil Defense – also known as the White Helmets – told the BBC that many of those killed were farmers and landowners trying to return to their lands after the fall of Assad’s regime.

The unexploded remains of war pose a serious threat to life in Syria. They are mainly divided into two types. The first is unexploded ordnance (UXO) such as cluster bombs, mortars and grenades.

Hassan Talfah, head of the White Helmets clearing mines in northwestern Syria, explained that clearing these devices is less difficult because they are often visible on the ground.

The White Helmets said that from November 27 to January 3, they cleared approximately 822 UXOs in northwest Syria.

Mr. Talfah said the bigger challenge lies in the second type of ammunition – landmines. He explained that government forces had previously planted hundreds of thousands of them across different areas in Syria – mainly on agricultural land.

According to the White Helmets, most of the deaths recorded since the fall of the Assad regime have occurred on the former front lines of combat. Most of those killed were men.

Mr. Talfah led us to two large fields full of mines. Our car followed him on a long, narrow and winding dirt road. That is the only safe way to reach the field.

Along both sides of the road, children ran and jumped around the area. Hassan told us they were from families who had recently returned. But the danger of mines always surrounds them.

As we got out of the car, he pointed to a barrier in the distance.

“This is the final point separating the areas under the control of government forces from those held by opposition groups” in Idlib province, he told us.

He added that Assad’s forces had placed thousands of mines in the fields outside the fence to prevent rebels from advancing.

The fields around where we stood were once important agricultural land. Today, they are all barren, with no trees except the green tops of the land mines that we can see with binoculars.

Without expertise in demining, all the White Helmets can do now is delineate these fields and post signs along the border warning people to leave.

They also sprayed warning paint on dirt barriers and houses around the edge of the field. They read: “Danger – there are mines ahead.”

They lead campaigns to raise awareness among local people about the dangers of entering contaminated land.

On the way back, we met a farmer about 30 years old who had just returned. He told us that some of the land belonged to his family.

“We couldn’t recognize any of it,” Mohammed said. “We used to grow wheat, barley, fennel and cotton. Now we cannot do anything. And as long as we cannot cultivate these lands, we will always be in a bad economic situation. poor,” he added, clearly disappointed.

White Helmets said they have identified and sealed off about 117 minefields in just over a month.

They are not the only ones working on demining, but there appears to be little coordination between the efforts of different organizations.

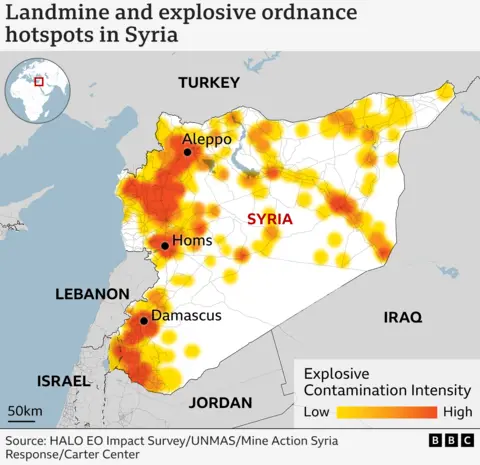

There are no accurate statistics on areas contaminated with UXO or landmines. But international organizations, such as the Halo Trust, have drawn up approximate maps.

Halo Syria program director Damian O’Brien said a comprehensive survey was needed for the country to understand the scale of the contamination. He estimates that about a million devices would need to be destroyed to protect civilian lives in Syria.

“Any Syrian military position is likely to have a number of mines placed around it as a defensive technique,” Mr. O’Brien said.

“In places like Homs and Hama, there are many neighborhoods that are almost completely destroyed. Anyone who goes into those structures to assess whether they are destroyed or rebuilt, needs to knowing that there may be unexploded ordnance in there, whether it’s bullets, cluster bombs, grenades, artillery shells.”

BBC news

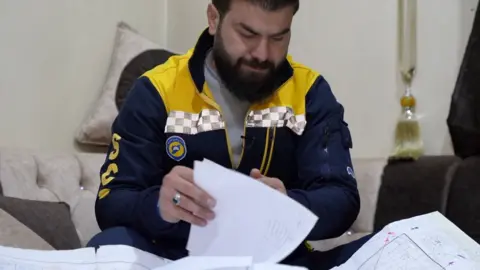

BBC newsThe White Helmets stumble upon a treasure that could aid demining efforts. At their office in Idlib city, Mr. Talfah showed us a stack of maps and documents left behind by government forces.

They show the location, number and type of mines planted in different fields across northwestern Syria.

“We will hand over these documents to the agencies dealing with landmines directly,” Mr. Talfah said.

But existing local expertise in Syria appears insufficient to counter the serious dangers that unexploded munitions pose to civilian life.

Mr. O’Brien emphasized that the international community needs to cooperate with the new government in Syria to improve the level of expertise in the country.

“What we need from donors is capital to be able to expand capacity, which means hiring more people, buying more machines and operating over a wider area,” he said.

For Mr. Talfah, clearing landmines and raising awareness of their dangers has become a personal mission. Ten years ago, he lost his leg while clearing cluster bombs.

He said that his injuries, and all the heartbreaking incidents he witnessed of children and civilians affected by UXO, only made him persistent in continuing to work.

“I never want any civilian or team member to go through what I went through,” he said.

“I cannot describe how I felt when overcoming a danger that threatened the lives of civilians.”

But until international and local efforts are coordinated to neutralize the dangers of landmines, the lives of many civilians, especially children, remain in danger.