The Greystone Mansion Murders of 1929: Mr. Plunkett, in the Study, With the Gun?

Around thirty-six hours after the killings and countless screaming headlines later, the District Attorney’s office and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department marked the inquest officially closed. The deaths of Ned Doheny and Hugh Plunkett were declared “beyond all doubt” to be a homicide and suicide committed by Hugh.

After that, press coverage was as dead as the men Les White found on the floor of Greystone a day earlier. Yes, it all lined up quite neatly. But little of it lined up with the crime scene evidence that White himself had recorded.

Where the Bodies—and the Truth—Were Buried

As both men’s funeral services were conducted within three days of their deaths, other potentially telling details emerged. Ned’s elaborate requiem mass was held at St. Vincent’s, the grand and glorious Roman Catholic church his father gifted the community at a cost of $500,000, near E.L.’s Chester Place compound and Ned’s alma mater USC, which canceled classes that Tuesday morning so faculty and students could pay last respects. Curious onlookers lined the streets as the church’s pews and aisles filled to capacity with invited mourners. Ned’s widow, Lucy, arrived, head to toe in black and wreathed in heavy mourning veils, accompanied by her mother-in-law Estelle, both softly sobbing. Leaning on the arms of friends for support, the patriarch himself, Edward L. Doheny Sr., appeared next. He was a sad, broken figure shuffling slowly, head bent low, face creased with grief. It was not lost on anyone who laid eyes on the aged tycoon how the once determined, hard-driving man who’d accumulated so much was so visibly bereft at the loss of his heir. It offered little solace that E.L. would, from that point on, be regarded with deep public sympathy, seen as having paid the ultimate price for whatever sins he may have committed during his ascent.

Following the mass, a smaller band of mourners drove to a private ceremony—ensured so by security guards—at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale. As devoutly Catholic as his last rites had been, it was a bit of a surprise that Ned would not go to Cavalry Cemetery, the prominent Catholic high society resting place east of downtown. His casket was instead delivered to the more broadly Christian (yet still segregated) Forest Lawn, interred on the rolling green knoll Sunrise Slope in the Temple of Santa Sabina. One day later, a few hundred mourners assembled to pay respects to Hugh Plunkett with a private funeral service downtown, awash with flowers sent by the Doheny family in an apparent gesture of grace and goodwill. Hugh’s casket was transported to his final resting place, which by no small coincidence was also at Forest Lawn, in a modest plot near an olive tree just under fifty paces away from the mausoleum containing Ned Doheny’s remains. For seventeen years, one had never been far from the other’s side. Now they would be companions for eternity.

Within the year, Albert Fall was convicted of accepting a bribe in the Teapot Dome scandal, becoming the first former cabinet member to be sentenced to prison, but E.L. Dohney, still riding a wave of public sympathy, was acquitted. Though he’d escaped prison, the aged oilman—shattered since Ned’s death—remained a recluse, caged by increasingly spiraling health and abiding grief. On September 8, 1935, with his wife, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren at his side, Edward Lawrence Doheny, Sr., died at age seventy-nine, having lived twice as long as his son and then some.

Forget It, Les—It’s Greystone

To Leslie White it appeared that perhaps “Old Man Doheny” was too big to monkey with. It seemed Buron Fitts had caved to the tremendous political pressure a man as powerful and deep-pocketed as E.L. Doheny could exert, and let the truth be buried with both men. He wondered if Fitts, sitting amid the Doheny’s elite circle during Ned’s funeral, had even agreed to a payoff or future favor-trade. But White would later write he learned his boss had “made a valiant attempt to get at the truth; how valiant it took me a long time to appreciate.”

White stifled his moral outrage and tried to put the case behind him, teased and castigated by colleagues for his initial zeal to challenge the Dohenys’ script. “I was accused of everything from being a fake to a plain fool,” he’d reflect. “I was ready to agree with the latter definition.”

But White wasn’t the only one who believed a very different version of the officially recorded events had transpired at Greystone Mansion. As the story quickly passed from breaking news into local legend, speculation about exactly what happened between Ned and Hugh began to emerge.

Could the role of the killer and the victim have been reversed? Based on his reported telephone conversation with Lucy, Hugh had been particularly disturbed by something Ned said to him at his apartment. Was his temper and paranoia really exacerbated by drug use and sleeplessness, or was it possible, with the Teapot Dome trial looming over E.L. Doheny, that Hugh was being pressured to become conveniently unavailable to testify, in a sanitarium and out of reach of subpoenas and federal prosecutors? And if he wasn’t willing to commit himself, would Ned have his closest friend forcibly confined, possibly indefinitely, to shield the father to whom he owed ever greater fealty? Was Hugh pushing back, insisting on assurances he’d have a smooth path out of the asylum? Did he want money for his trouble?

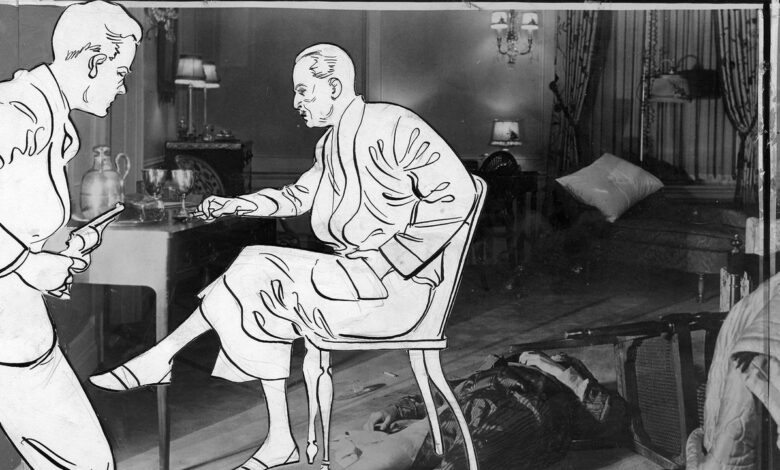

Did Hugh actually bring the Colt Bisley into the house to bolster his argument, or was Ned the one to retrieve it? Despite a potentially whitewashed coroner’s report, it appeared obvious that, over nearly ninety minutes together in the guest suite, both men had been drinking. Could it have instead been Ned who—under pressure himself and frustrated by Hugh’s intractability and the dire consequences it posed for his family—exploded in a fit of rage, further inflamed by scotch, and shot Hugh? Then, in a wave of remorse over snuffing out the life of his dearest friend, turned the pistol on himself, leaving the truth to be sanitized and obscured? With the Dohenys scarcely able to bear another scandal, was Ned’s body repositioned by his family’s factotums to appear more convincingly the victim, the gun wiped clean of prints, then heated in an oven in advance of the police arrival and stories gotten straight before interrogation?

Perhaps…? Possibly…? Maybe…?

The underground press also floated another theory that would gradually gain a foothold: did Ned and Hugh’s much-discussed closeness stem from a secret sexual relationship or concealed romance? “He acted as a secretary to Ned, but their relationship was more than that of friends,” Frederic R. Kellogg, one of E.L. Doheny’s longtime corporate attorneys, told the press obliquely in the wake of the killings. Certainly the notion of the inseparable secretary-companion was even then a familiar trope to cloak a closeted gay affair.

The rumor mill targeted the pair’s final resting places as a tantalizing clue: if Ned were gay it would be unthinkable to bury him on the consecrated ground of Calvary Cemetery, where all the Catholic power players of L.A. were interred, no matter what the official story was. This could have prompted his placement at Forest Lawn; if so, presumably the family quietly granted the proximity of Hugh’s grave there as well as an unspoken concession to keep them as close in death as in life.

The concept of a sexual relationship or passionate romance between Ned and Hugh is well within the realm of possibility. But no tangible evidence or anecdotal source ever emerged to concretely substantiate the conjecture. The cemetery arrangement? Suicide, too, was deemed a mortal sin, and if Ned had killed himself he would be denied a Catholic burial, which again could explain the choice of Forest Lawn. Perhaps the Dohenys had stage-managed the death scene to protect his public reputation but decided they couldn’t completely shield him from the judgment of their faith.

Perhaps. Possibly.

The Volume Vanishes

Leslie T. White tried to put the Greystone case behind him in the months that followed, continuing to do standout work for the district attorney’s investigation bureau. But eventually White resigned. “I like the work, but I hate the politics,” he told Fitts. “You can’t stay in it and be honest—not really honest…Sooner or later you get seriously jammed up. You know that better than I do.”

Even before he quit the D.A.’s unit, on the advice of his friend Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of fictional legal ace Perry Mason, he’d launched what would become a prolific and prosperous career as a writer: his stories—typically smartly plotted, authentically detailed detective yarns starring earnest straight-arrow sleuths who viewed justice in black-and-white terms, as he once had himself—were in high demand among pulp magazines’ editors.

In 1936 White published his hardboiled and candid—blunt, even—memoir. Me, Detective was a richly detailed, largely unsparing account of the political obstacles and corrupt hurdles that White faced as he tried to ferret out truth and dispense justice in several sensational cases well known to his reading public—including his previously unrevealed findings in the murder-suicide at Greystone. The book garnered rave reviews and sold briskly across the country – uniquely so in Los Angeles: Hugh Plunkett’s brother, unable to locate a single copy, would tell his family several booksellers informed him the Doheny family had purchased every copy in the region.

Pulp Fiction, Pulp Facts

Raymond Chandler, a former oil industry executive, and White’s shared professional interest in the volatile, perpetually scandalous L.A. crime scene of the day and the intrigue involving the Doheny family suggests they had plenty to talk about when they met during a gathering of Black Mask’s pulp writers in 1936. White must have mentioned that Me, Detective was due to be published in August, and it seems Chandler eventually got his hands on the memoir. Because the Dohenys and their showy displays of wealth and dominant exertion of power were catnip to Chandler, his fascination eventually began to find expression in his own writing.

Chandler’s descriptions in The Big Sleep of the estate of the Sternwood family, whose fortune was built on oil, are specifically evocative of Greystone Mansion, closely capturing its luxuries and imposing ambiance. Later, through his sleuth Phillip Marlowe’s sardonic take on the Grayle estate in Farewell, My Lovely, Chandler echoed White’s impression of Greystone: “It was smaller than Buckingham Palace, rather gray for California, and probably had fewer windows than the Chrysler Building.” Clearly, White—like Marlowe, a former investigator for the D.A.’s office whose uncompromising moral code set him on his own path—made an indelible impression on Chandler.

Finally, in a passage within his 1942 novel The High Window, Chandler went even further, putting forth a full-throated interpretation of what happened at Greystone. Here’s Marlowe discussing the “Cassidy case” with a cop named Breeze.

Breeze sighed. “Murder and suicide during a drinking spree. The secretary went haywire and shot young Cassidy. I read it in the papers or something. Is that what you want me to say?”

“You read it in the papers,” I said, “but it wasn’t so. What’s more you knew it wasn’t so and the D.A. knew it wasn’t so and the D.A.’s investigators were pulled off the case within a matter of hours. There was no inquest. But every crime reporter in town and every cop on every homicide detail knew it was Cassidy that did the shooting, that it was Cassidy that was crazy drunk, that it was the secretary who tried to handle him and couldn’t and at last tried to get away from him, but wasn’t quick enough. Cassidy’s was a contact wound and the secretary’s was not. The secretary was left-handed, and he had a cigarette in his left hand when he was shot. Even if you are right-handed, you don’t change a cigarette over to your other hand and shoot a man while casually holding the cigarette. They might do that on ‘Gang Busters,’ but rich men’s secretaries don’t do it. And what were the family and the family doctor doing during the four hours they didn’t call the cops? Fixing it so there would only be a superficial investigation. And why were no tests of the hands made for nitrates? Because you didn’t want the truth. Cassidy was too big. But this was a murder case too, wasn’t it?”

“The guys were both dead,” Breeze said. “What the hell difference did it make who shot who?”

“Did you ever stop to think,” I asked, “that Cassidy’s secretary might have had a mother or a sister or a sweetheart—or all three? That they had their pride and their faith and their love for a kid who was made out to be a drunken paranoiac because his boss’s father had a hundred million dollars?”

It took Chandler’s noir fiction to at long last depict the plausible noir reality that unfolded in the hulking, fortress-like estate looming above Beverly Hills, ever-emanating overwhelming privilege and power. But the truth remained as elusive and unknowable as ever.

And while he was never the literary stylist Chandler was, White succinctly captured the conundrum when justice and money—lots and lots of money—collided: “You can’t convict a million dollars.”

Excerpted from Beverly Hills Noir by Scott Huver. Published by Post Hill Press Used with permission.

All featured products are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, Vanity Fair may earn an affiliate commission.